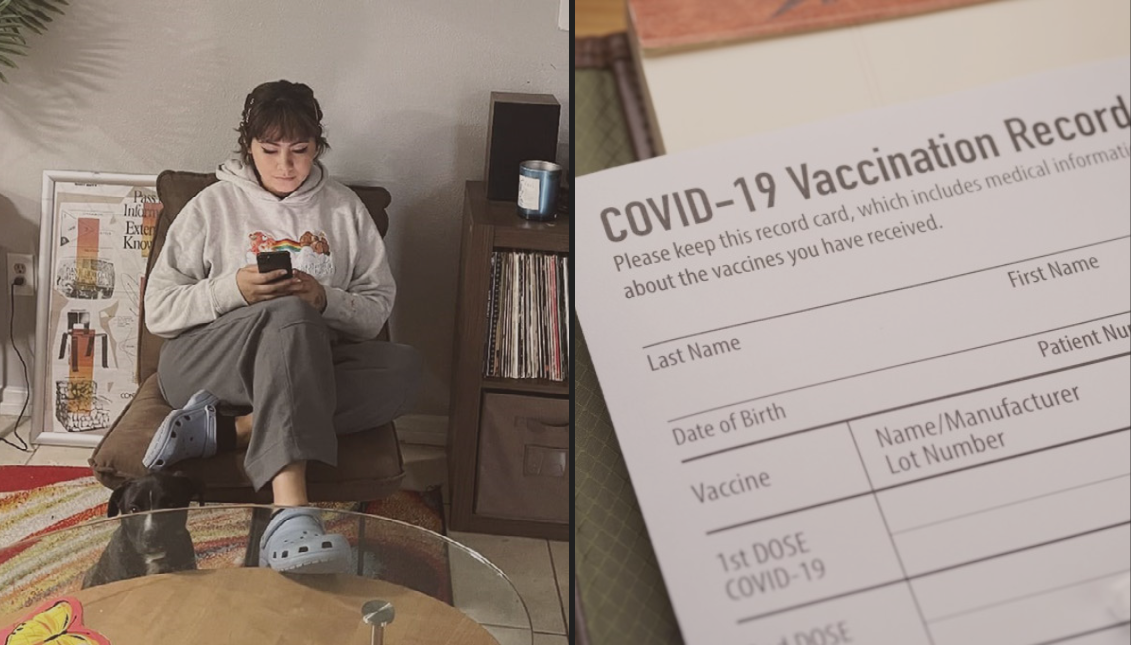

The 26-year-old Latina finding COVID vaccines for her Rio Grande Valley community

Selina Herrera has used a Google form to sign members of her community up for COVID-19 vaccines.

Selina Herrera, a young Latina Texas resident, has single handedly helped more than 600 people receive COVID-19 vaccines in the Rio Grande Valley area.

Her outstanding work began at home, when she noticed that her older tíos were having trouble finding appointments for COVID-19 vaccines. But helping out her family was just the start of her vital servitude, especially for fellow Latino families in her area.

The 26-year-old began her volunteer journey after registering her family for appointments — as she is the most tech savvy.

It was then that she realized something crucial — if her Latino family was struggling to schedule vaccine appointments, and she had the spare time to help them — she could easily help to register others who may also be at a loss.

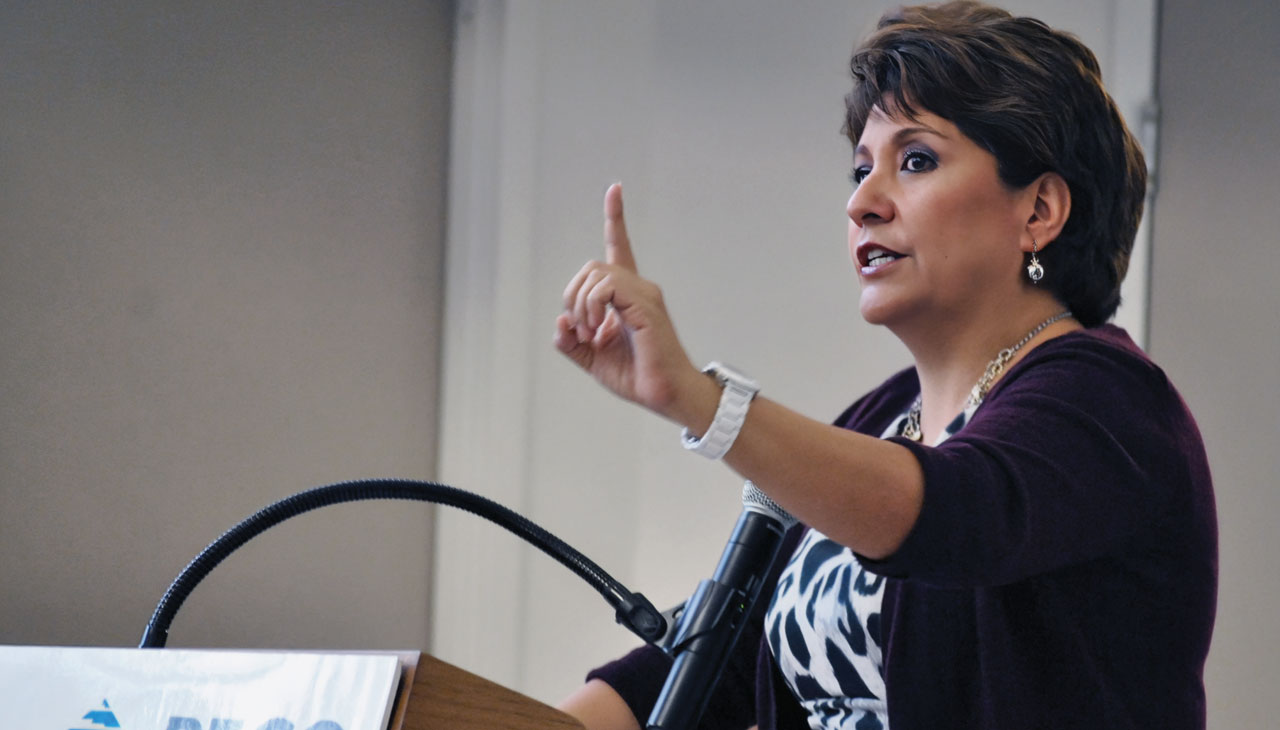

Despite the systemic barriers and challenges, Selina Herrera and rising Latina leaders like her across the country continue to forge ahead and get results. They give me hope for the future.

— Nathalie Rayes (@NathalieRayes) April 3, 2021

Thank you, thank you, thank you — Selina! https://t.co/ArSDIXDjkJ

Herrera says the people she works with have struggled with both online vaccine registration and in-person events.

She mainly served marginalized communities, such as native Spanish speakers facing a language barrier, elderly people, and people with disabilities.

“I’ve been fortunate enough to be able to catch these appointments for them, and I just have to thank my really fast thumbs and super speed internet, which I know many people [do not] have,” she said.

What is the work?

The technologically-skilled millennial launched her initiative with a tool that many of us have at our fingertips — her iPhone. Using her smartphone, Herrera created a Google form at the beginning of March to schedule appointments.

The form includes basic contact and health information, as well as the distance an applicant is willing to travel to get vaccinated.

On a daily basis, Herrera does this volunteer work during her lunch hour or in the evening after her full-time job, which involves providing assessment for case workers that work with clients enrolled in programs like SNAP or Medicaid.

On the weekends though, she dedicates her time solely to facilitating appointments through the Google form.

Most of her applicants are Latino, as they make up the overwhelming majority of the population in the Rio Grande Valley area — a region on the southern border of Texas above Mexico.

Many of the applicants Herrera signed up came through people she already knew. Sometimes an applicant would be signed up by a relative who didn’t know about her initiative, and they were taken aback when Herrera would inform them of their appointment.

In several marginalized communities, especially among people of color and those with disabilities, there tends to be a lack of trust, especially when it comes to the medical industry and giving out sensitive personal information to strangers.

Today we began contacting the second half of Group 4 to schedule your vaccine appointments! Be sure to follow the instructions in the message you receive, but be careful of scams! We will never ask for your social security number or payment information. pic.twitter.com/zp24T6LshY

— Durham Public Health (@DurhamHealthNC) March 29, 2021

Herrera learned this early on when she began offering her services to people who didn’t know her. She often needed to assure them that she is a trustworthy community member, and had the appropriate skills to take care of their appointments.

Much of her day job involves ensuring that private information remains confidential. Herrera put a brief biography on the Google form to demonstrate her trustworthiness.

Experts have stated that the best way to get “hard-to-reach” communities vaccinated is through trusted sources, which can protect people from potential scammers.

Why is it so hard to find appointments?

Latino communities have been facing many obstacles when it comes to vaccine accessibility, leading to a large disparity in the groups receiving their doses, according to a report last month by The New York Times.

“There is limited access to the digital tools needed to secure an appointment, for instance, especially among those who are older and live in immigrant communities,” the report said.

RELATED CONTENT

This is where alternative resources shine. Healthcare advocates, community clinics, or a compassionate relative —like Herrera— play a significant role in reaching the populations that are underserved.

NEW: As of March 22, the federal Health Center COVID-19 Vaccination Program had provided over 1M doses to the 325 community health centers (CHCs) participating so far.

— KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation) (@KFF) March 31, 2021

75% of patients at the #CHCs were people of color.https://t.co/Y43p35HVdj pic.twitter.com/2ndSQBXLpY

The Biden’s administration recently established an initiative to direct more doses to community clinics, which have historically played critical roles in serving Latino, Black, AAPI, and low-income communities.

According to an analysis of federal data by the Kaiser Family Foundation, Hispanic people make up 18% of the U.S. population, but they make up more than a quarter of those nationwide that have received their first dose at a community health center.

How does she help applicants?

The main barrier that Rio Grande Valley residents are facing is limited appointment times. Many residents have been going to sites that offer vaccines on a first-come, first-serve basis, but require people to wait in line for hours.

Unfortunately, waiting in line for long periods of time doesn’t even guarantee that people will get a vaccine that day. Adding more frustration, people often have to take time off from work and use public transportation, which requires planning and money that some people may not have to spare.

When applicants fill out Herrera’s Google form with their information and preferences, she fishes for online appointments, searching company sites like Walgreens and CVS until she finds one that matches their distance preference and time availability.

Once a spot is confirmed, Herrera will text or call them, and she can do so in Spanish, which is often met with a huge sigh of relief.

In the briefing: Black and Latino Americans face more barriers when getting a coronavirus vaccine. For Latinos, the language barrier faced when going through the process is evident because many websites to make appointments are only available in English. https://t.co/Re5xcqW2bZ

— Christina Morales (@Christina_M18) February 18, 2021

Applicants will sometimes offer Herrera things as a sign of gratitude, but she always refuses, insisting that “it’s no big deal.”

The number of applicants comes in waves and Herrera isn’t sure of the specific number of people she has registered. She lost count after 440, but it’s certainly well above 600 by now.

While she’s not sure if this will last for the rest of the year, she’s happy to keep doing it for as long as she can.

"For every person I’m helping, that’s one less person that's reaching out or that needs to be vaccinated," Herrera said.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.