Philly’s one-of-a-kind Driving Equity bill takes effect

The bill, passed by City Council in October 2021, bans police stops for seven minor motor vehicle violations.

After 120 days for police training and implementation, Driving Equality is an enforceable law in Philadelphia as of Thursday, March 3.

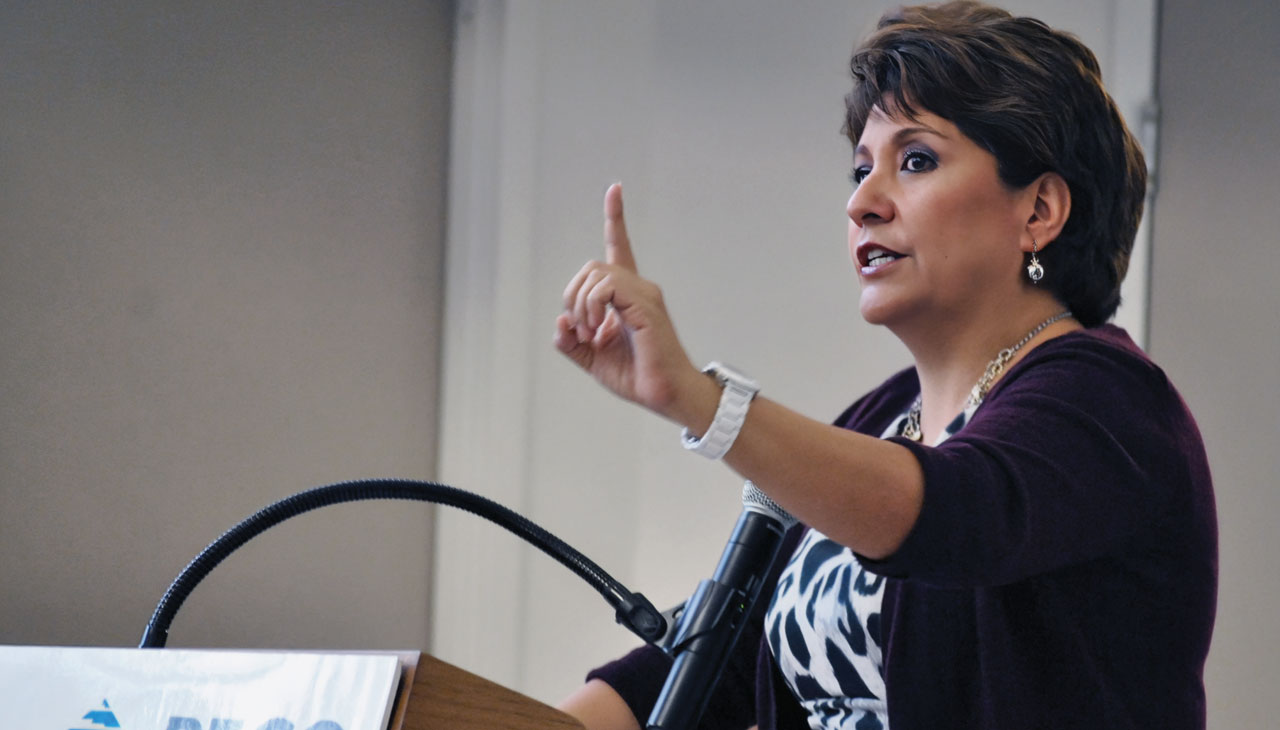

Last October, City Council passed Councilmember Isaiah Thomas’ Driving Equality bills with an overwhelming majority. Mayor Jim Kenney then cemented the law with an executive order last November.

The City Council bills and Mayoral executive order gave Philadelphia Police three months for training and education before enforcing Driving Equality.

#DrivingEquality is now the law in Philly.

— Councilmember Isaiah Thomas (@CMThomasPHL) March 3, 2022

We've reclassified 8️⃣ traffic violations to promote equality on our streets.

Thank you @PhillyMayor , @PPDCommish, @PHLCouncil, @PhillyPolice, @PhillyDefenders, @PhiladelphiaGov & all who made this possible! https://t.co/BEgetXLawC

The new law reclassifies seven minor motor vehicle code violations as secondary violations which will not be administered with a traffic stop. These violations include past due emission and inspection stickers, late registration, having one tail light out, items hanging from the rearview mirror, and more.

Similar to Pennsylvania seat belt laws, these are still violations but would be enforced with methods other than a traffic stop.

Philadelphia is now the first big city to have this kind of policy. While it was introduced and championed by Thomas, the bill was crafted in collaboration with the Philadelphia Police Department (PPD) and the Defender Association of Philadelphia.

The Defender Association examined 309,000 stops using information collected by the PPD from traffic stops between October 2018 and September 2019.

Their analysis showed that Black drivers were stopped the most, representing 72% of the stops, compared to 15% of white drivers.

In a February press release, Thomas said that as a coach, he often has a whistle hanging from his mirror, which is the same motor vehicle code violation that initiated the traffic stops that led to the deaths of Daunte Wright, Philando Castile and so many others.

RELATED CONTENT

Today #DrivingEquality is the law. We've worked to reclassify the traffic stops that promote discrimination and keep the ones that keep us safe.

— Councilmember Isaiah Thomas (@CMThomasPHL) March 3, 2022

Philly can often be a tale of two cities for Black and Brown folks. Today, we take a giant step to bridge the divide. pic.twitter.com/yP7KtA8ix0

“Many traffic stops are traumatic and, since they are oftentimes a person of color’s first interaction with law enforcement, start off a tense relationship. By removing the stops that promote discrimination rather than public safety, we can rebuild police-community trust,” Thomas said.

If one of these codes is the only wrongdoing a driver is committing on the road, police are no longer allowed to pull them over. If a driver violates any other aspects of the code like running red lights or speeding, they can be stopped, and police can cite them for multiple infractions.

Thomas’s office is also establishing a working group to track the policy’s implementation and the new data Driving Equality will produce.

“This group is a combination of academics and experts, but also concerned citizens,” said Max Weisman, director of communications for Thomas’ office. Weissman said that members of the group should be announced by the end of March.

The primary catalyst behind the Driving Equality law is the experience that many Black and Brown drivers in Philadelphia have grown very familiar with: being pulled over for harmless violations that lead to prolonged stops and searches.

Relations between communities of color and police are tense due to the history and persistence of many forms of discrimination and brutality, and the objective of the law is to decrease these encounters.

Thomas, who has been pulled over many times in Philly, told NPR that he hopes the law will help restore trust between police and communities of color.

“We’re excited about what we are possibly able to do as it relates to not just reducing traffic stops and minimizing negative interactions between communities of color and law enforcement, but just overall changing the narrative as it relates to the relationship between the two,” he said.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.