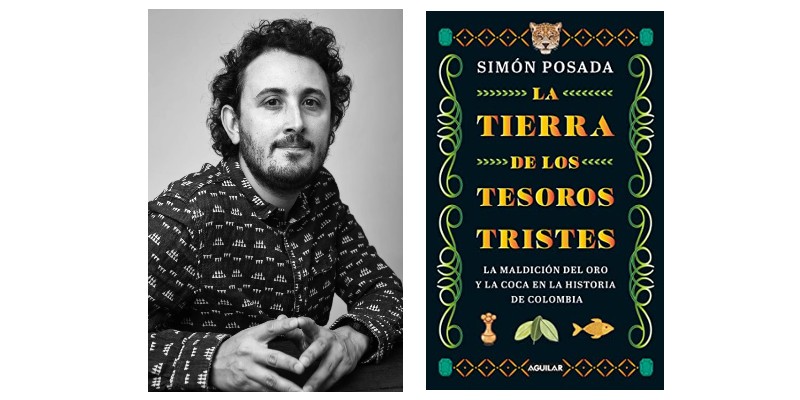

Colombia, Land of Sad Treasures

Colombian writer Simón Posada narrates the negative impact of gold and coca in the history of Colombia

Why are we so poor if we are so rich? This is one of the questions Colombian journalist and writer Simón Posada wanted to answer in his new book, “La tierra de los tesoros tristes: la maldición del oro y la coca en la historia de Colombia” (Aguilar, 2022), where he explores the tragic role of gold and coke in his country since the times of the Spanish conquest.

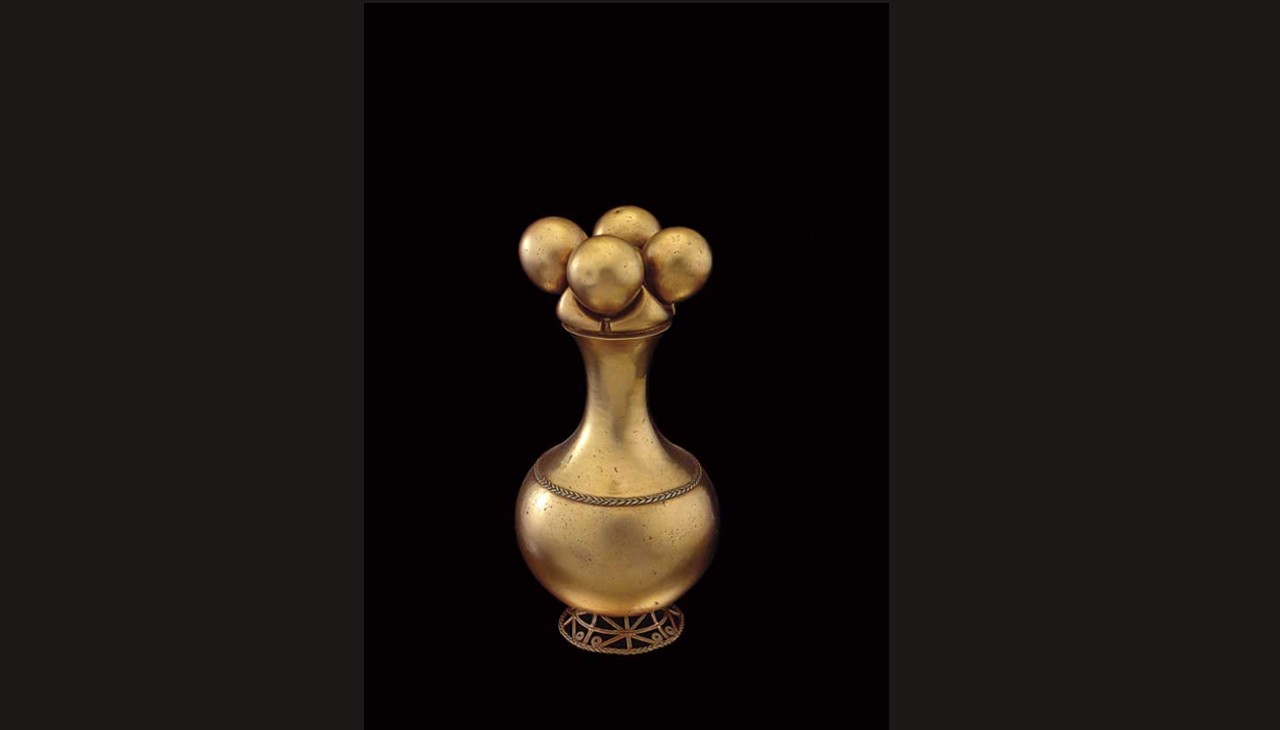

Following the story of the so-called Poporo Quimbaya, one of the country’s most prized pre-Columbian gold relics, the author narrates how the Spanish colonizers exploited the powerful relationship of the Indians, coke and the gold coffers of the empire, and consequently, of treasure hunters, tomb raiders and forgers, and how coke and gold ended up becoming Colombia’s great curse because of its environmental, political, economic and social repercussions.

How did the idea for this book come about? How did you become interested in the Quimbaya poporo?

In 2012, I was working as a nonfiction editor at Grupo Planeta and I had a Peruvian boss, Sergio Vilela, who had published a very successful book in Peru about Machu Picchu. Vilela, as an immigrant in Colombia, wondered a lot about a particular object or site that was very symbolic of Colombian identity. I left Planeta afterwards and I was left with that concern. On a visit to the Museo del Oro, a guide told me that the poporo had been sold to the Bank of the Republic by one of the daughters of Coriolano Amador, one of the richest men in Colombia in the 19th century, owner of perhaps the

most productive gold mine in Colombia at that time, the El Zancudo mine. So rich was that mine that they began to issue currency and people in the region bought things with bills from the mine, which had Coriolano Amador’s face printed on them. At that moment I started to look into his life, which was fascinating, and that’s when I said: “this is a book”.

Why the title “The land of sad treasures”?

Because that is the feeling that remains when you review our [Colombia’s] history and see all our riches, and you can only wonder: why are we so poor if we are so rich? Also because the sensations that remain from a visit to the Gold Museum or from the study of these peoples and what happened since the conquest generates a lot of contradictory feelings: amazement at the beauty of the pieces, sadness because those pieces were in a tomb of someone who was raped, sadness for all the other tombs that were desecrated and for all the other pieces that were lost forever.

Why is it important to keep revisiting/ researching the history of a country?

RELATED CONTENT

The answer, unfortunately, is a catch phrase: a country that does not know its history is condemned to repeat it. As simple and cliché as that. But I also believe that the history of Colombia is sufficiently documented, but it is written in a language for academics, which rarely reaches the general public. In my book I did not discover anything, I only made curious relationships of data and, at least I think so, I managed to land very complex things to explain in a clear language for the general public. I think that is the value of this book, being a work of popular science that can be read easily and quickly in an era in which we are all unfocused because of phones and screens.

Why did you become a journalist?

I decided to become a journalist because it is a profession where it is possible for every day to be different. After 17 years in the profession, I can say that I have been lucky enough to have a very non-routine day. I also became a journalist because I wanted to be a fiction writer, but I fell in love with non-fiction and I don’t think I will move from there.

You work for international media. Have you ever considered emigrating abroad?

At the moment I work for cambiocolombia.com, a political digital magazine in Colombia. In 2016 I emigrated to Miami, where I worked two years for Univision. Then, I worked eight months at BBC News Mundo and one more year for CNN en Español. It was a very hard and very enriching experience, where, in addition, I met my wife (Italian-American-Colombian). I don’t chase the American dream, but if it chases me, I let it catch me. I loved living in the United States and I would do it again if the opportunity comes. If it doesn’t come, that’s fine, I love Colombia, I’m very happy here and I have a privileged and comfortable life.

What interest can this book have for the Latino reader in the United States?

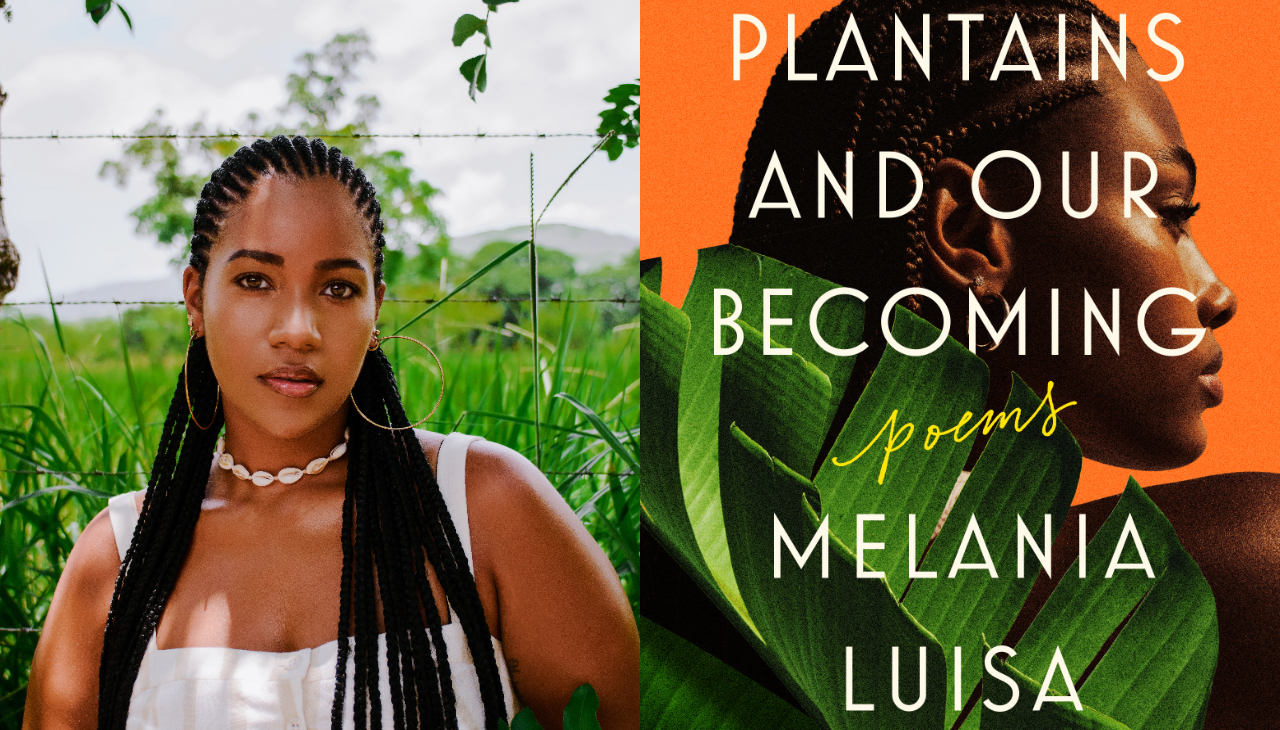

All Latin countries, because of theircolonial past, have stories of sad treasures, of lost treasures, of those whose history is unknown and that were left in limbo in time. I believe that in my book Latinos can find a mirror of their place of origin, no matter where they were born. From Argentina to Mexico we have lived through plundering, lack of identity and ignorance of who we are, where we come from and where we are going. My book helps to mourn all these losses. Now, specifically for Colombians, the subject of how gold and coke have governed our country is very valuable

to address, because it makes us aware of dynamics under which we act, but of which perhaps we have not been aware, such as careerism and the desire for wealth above anything else.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.