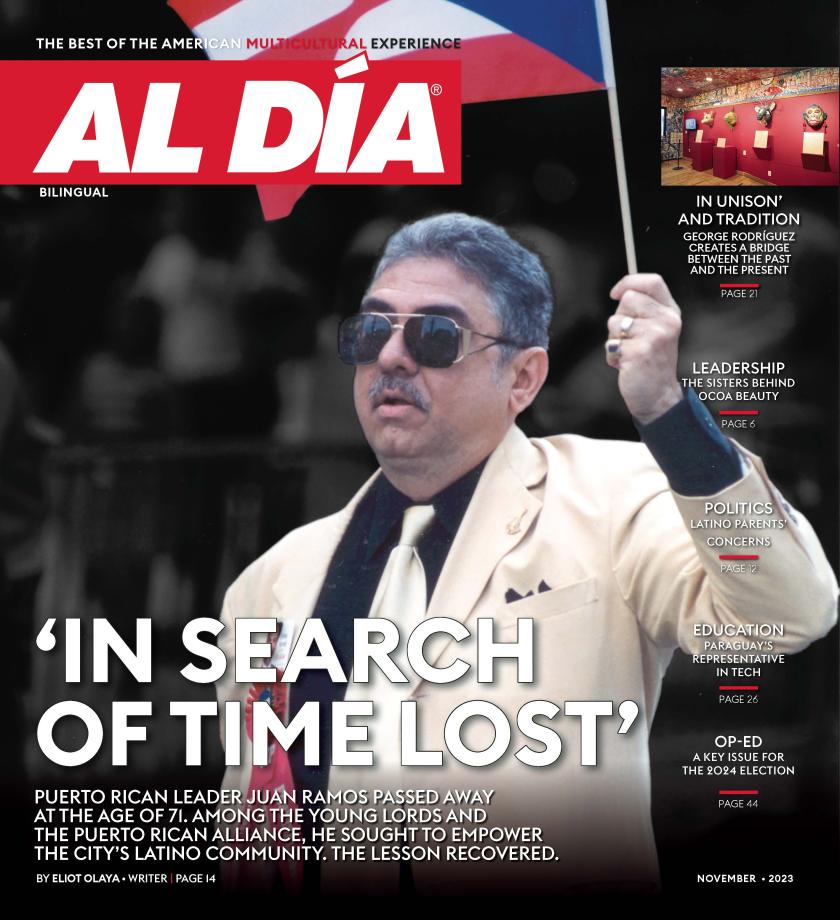

The ‘García Márquez Newsroom’ at AL DÍA

I recently walked by the house Gabriel García Márquez owned and used to stay at in Cartagena, Colombia, and I couldn’t wait to get to the keyboard to tell a…

I recently walked by the house Gabriel García Márquez owned and used to stay at in Cartagena, Colombia, and I couldn’t wait to get to the keyboard to tell a personal story about this maestro of good literature and even better journalism.

I grew up reading “Gabo,” as he was known to his friends. Not so much the fiction — which gave him a Nobel Prize for Literature and a celebrity status around the world he ended up resenting — but his journalism. That was a required textbook for generations of aspiring reporters across the continent trying their hand in the practice of what is also known as the “first draft of history.”

I remember justifiably skipping Catholic Mass on Sunday to read the syndicated column he wrote for El País — which was sort of our own Gospel — when I was just a teenager, but already enrolled in a school of journalism in Bogotá, Colombia.

Gabo’s dose of 600 words every week was a matter of survival, a stop in the oasis of his writing while living in that very solitary and arid desert Bogotá was...

In that remote and enormous metropolis, far away from the province of Santander where I was born and raised, to read Gabo’s dose of 600 words every week was a matter of survival, a stop in the oasis of his writing while living in that very solitary and arid desert Bogotá was to me during my college years.

He captivated the imagination of the young journalism student with the tales of his life: Law school drop-out and also rebel against his father’s will (who was determined to make him, the oldest in the family of 11 brothers and sisters, an example to the other siblings by forcing him to practice a "decent profession").

"Gabo," as he as known in Colombia, the young reporter photographed holding a lit cigarette between his clenched teeth while dispatching — on the keyboard of his mechanical typewriter— the latest news of the day. Or the mature Gabo, still in his late 20s, confronting an entire military government in Colombia armed himself only with the power of his rich imagination — telling a revealing story serialized in "El Espectador" under the title "Relato de un Náufrago" (1970), and demolishing week to week, keystroke by keystroke, the “official” version of the truth pushed by that national government and its Ministers of Propaganda.

His love for journalism and newspapers competed with his obvious and secret passion to dive deeper and live for months, or years, in his greenhouse of his imagination and the pure fiction he was also capable of crafting, so that he could take full revenge and make his stories eternal, unbound by time and space, and also free from the fatuous and mortifying pressures of worldly powers.

But eventually and naturally fed-up by the solitary exercise of writing just literature in the confinement of his studio, García Márquez would always return with renewed enthusiasm to journalism, his first love, and to his friend, his lifeblood, perhaps to replenish and reconnect with the real world, live and be whole again.

When he won the Nobel Prize for Literature, he announced he would dedicate the sizable prize cash award he earned to a unique newsroom “where the average of the reporters was 25 years of age.”

When he won the Nobel Prize for Literature, on Dec. 8, 1982, at the age of 54, he announced he would dedicate the sizable prize cash award he earned to the foundation of a unique newsroom “where the average of the reporters was 25 years of age.”

Like many other projects he left unfinished or pending, this news organization he imagined never became a reality. He ran out of time, or patience (or both) to enact such a daring project in Latin America.

Two years ago, when García Márquez died in Mexico City, an idea naturally came to us here in Philadelphia where AL DÍA News is produced:

Since we had been putting together for two decades — without fully realizing it — that imagined newsroom of Gabo’s where people who crafted the news of the day were of young professionals in their mid 20s, we decided that we may as well do justice to him our own away and memorialize him in the City of Brotherly Love by calling our young and audacious newsroom the “García Márquez Newsroom.”

“The interpretation of our reality through patterns not our own, serves only to make us ever more unknown, ever less free, ever more solitary.”

What a high calling for all of us this could become, once everybody who works here came to understand the legacy of this master who left us two years ago, and the fundamental purpose of this dual language news organization that spontaneously was born in the Latino neighborhood 23 years ago.

The affinity of the AL DÍA experience, and the life of American of Latino descent living today in the United States, and the life of "Gabo" grew stronger when said, when he received the Nobel Prize in Sweden, 34 years ago:

“The interpretation of our reality through patterns not our own, serves only to make us ever more unknown, ever less free, ever more solitary.”

We prefer to remember him as the man who “owing to his hands-on experiences in journalism, is, of all the great authors, the one who is closest to everyday reality,” as literary critic Bell-Villada aptly put it.

LEAVE A COMMENT:

Join the discussion! Leave a comment.